In this article we will discuss what Charlotte Mason had to say about the Alphabet. Then I will talk to you about the alphabet cards available on the store and how to pronounce the French alphabet.

The Alphabet and reading: what did Charlotte Mason say?

In her Volume 1, pages 201-202, Charlotte Mason has a whole section entitled “The Alphabet”. These extract come from the website Ambleside Online.

The Alphabet.––As for his letters, the child usually teaches himself. He has his box of ivory letters and picks out p for pudding, b for blackbird, h for horse, big and little, and knows them both. But the learning of the alphabet should be made a means of cultivating the child’s observation: he should be made to see what he looks at. Make big B in the air, and let him name it; then let him make round O, and crooked S, and T for Tommy, and you name the letters as the little finger forms them with unsteady strokes in the air. To make the small letters thus from memory is a work of more art, and requires more careful observation on the child’s part. A tray of sand is useful at this stage. The child draws his finger boldly through the sand, and then puts a back to his D; and behold, his first essay in making a straight line and a curve. But the devices for making the learning of the ‘A B C‘ interesting are endless. There is no occasion to hurry the child: let him learn one form at a time, and know it so well that he can pick out the d’s, say, big and little, in a page of large print. Let him say d for duck, dog, doll, thus: d-uck, d-og, prolonging the sound of the initial consonant, and at last sounding d alone, not dee, but d‘, the mere sound of the consonant separated as far as possible from the following vowel.

Let the child alone, and he will learn the alphabet for himself: but few mothers can resist the pleasure of teaching it; and there is no reason why they should, for this kind of learning is no more than play to the child, and if the alphabet be taught to the little student, his appreciation of both form and sound will be cultivated. When should he begin? Whenever his box of letters begins to interest him. The baby of two will often be able to name half a dozen letters; and there is nothing against it so long as the finding and naming of letters is a game to him. But he must not be urged, required to show off, teased to find letters when his heart is set on other play.

In section VI entitled Reading by sIght and Sound, Charlotte Mason says :

Learning to read is Hard Work.––Probably that vague whole which we call ‘Education’ offers no more difficult and repellent task than that to which every little child is (or ought to be) set down––the task of learning to read. We realise the labour of it when some grown man makes a heroic effort to remedy shameful ignorance, but we forget how contrary to Nature it is for a little child to occupy himself with dreary hieroglyphics––all so dreadfully alike!––when the world is teeming with interesting objects which he is agog to know. But we cannot excuse our volatile Tommy, nor is it good for him that we should. It is quite necessary he should know how to read; and not only so––the discipline of the task is altogether wholesome for the little man. At the same time, let us recognise that learning to read is to many children hard work, and let us do what we can to make the task easy and inviting.

Knowledge of Arbitrary Symbols––In the first place, let us bear in mind that reading is not a science nor an art. Even if it were, the children must still be the first consideration with the educator; but it is not. Learning to read is no more than picking up, how we can, a knowledge of certain arbitrary symbols for objects and ideas. There are absolutely no right and necessary ‘steps’ to reading, each of which leads to the next; there is no true beginning, middle, or end. For the arbitrary symbols we must know in order to read are not letters, but words. By way of illustration, consider the delicate differences of sound represented by the letter ‘o’ in the last sentence; to analyse and classify the sounds of ‘o’ in ‘for,’ ‘symbols,’ ‘know,’ ‘order,’ ‘to,’ ‘not,’ and ‘words,’ is a curious, not especially useful, study for a philologist, but a laborious and inappropriate one for a child. It is time we faced the fact that the letters which compose an English word are full of philological interest, and that their study will be a valuable part of education by-and-by; but meantime, sound and letter-sign are so loosely wedded in English, that to base the teaching of reading on the sounds of the letters only, is to lay up for the child much analytic labour, much mental confusion, due to the irregularities of the language; and some little moral strain in making the sound of a letter in a given word fall under any of the ‘sounds’ he has been taught.

Definitely, what is it we propose in teaching a child to read? (a) that he shall know at sight, say, some thousand words; (b) That he shall be able to build up new words with the elements of these. Let him learn ten new words a day, and in twenty weeks he will be to some extent able to read, without any question as to the number of letters in a word. For the second, and less important, part of our task, the child must know the sounds of the letters, and acquire power to throw given sounds into new combinations. What we want is a bridge between the child’s natural interests and those arbitrary symbols with which he must become acquainted, and which, as we have seen, are words, and not letters.

These Symbols should be Interesting.––The child cares for things, not words; his analytic power is very small, his observing faculty is exceedingly quick and keen; nothing is too small for him; he will spy out the eye of a fly; nothing is too intricate, he delights in puzzles. But the thing he learns to know by looking at it, is a thing which interests him. Here we have the key to reading. No meaningless combinations of letters, no cla, cle, cli, clo, clu, no ath, eth, ith, oth, uth, should be presented to him. The child should be taught from the first to regard the printed word as he already regards the spoken word, as the symbol of fact or idea of full of interest. How easy to read ‘robin redbreast,’ ‘buttercups and daisies’; the number of letters in the words is no matter; the words themselves convey such interesting ideas that the general form and look of them fixes itself on the child’s brain by the same law of association of ideas which makes it easy to couple the objects with their spoken names. Having got a word fixed on the sure peg of the idea it conveys, the child will use his knowledge of the sounds of the letters to make up other words containing the same elements with great interest. When he knows ‘butter’ he is quite ready to make ‘mutter’ by changing the b for an m.

The bilingual alphabet

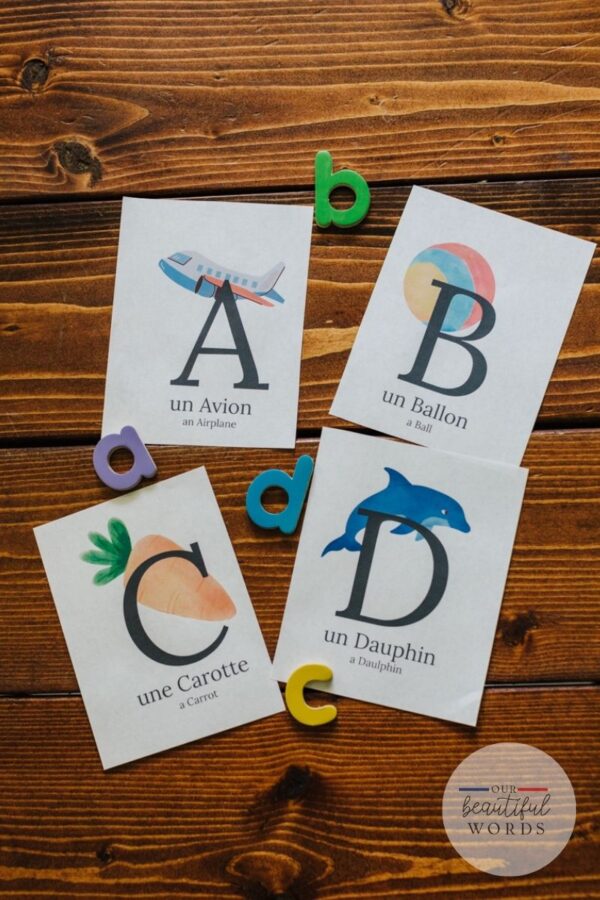

I decided to create bilingual cards because when you learn French with English books, it’s not always easy to make sense for your child. Especially when you use an English book teaching about the alphabet but you’re trying to use it to also mention the French pronunciation of the alphabet.

For example, A – an Apple but in French it’s translated into une Pomme. And that is just confusing for a child learning the alphabet.

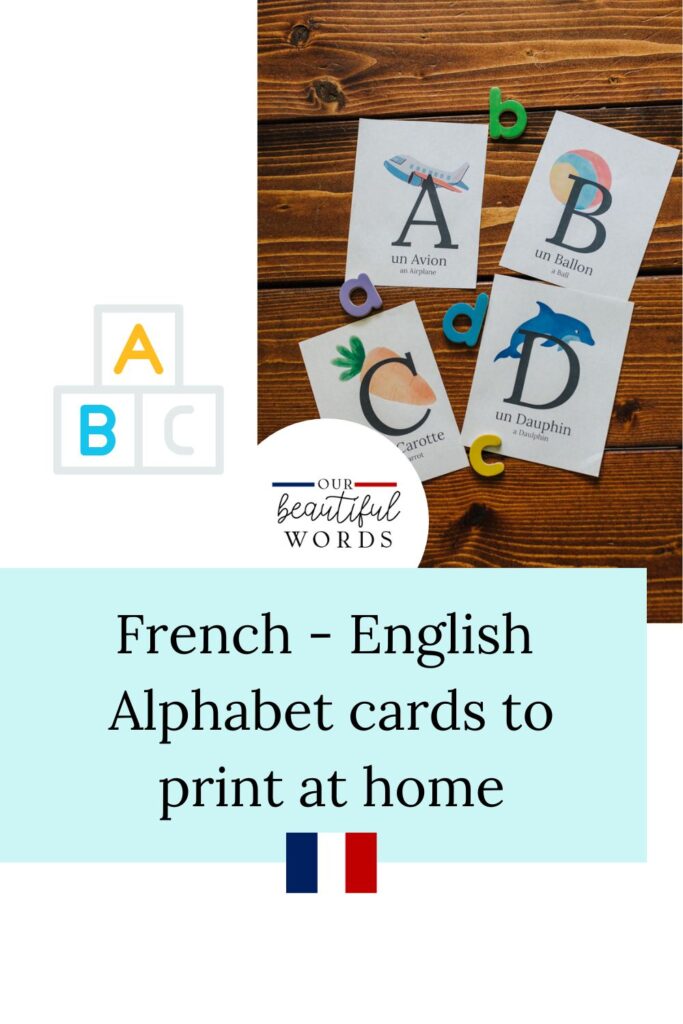

So I created cards that you can download and print from the Shop. Their particularity ? For each letter of the alphabet, I found a word in English and French that has the same meaning and start with the same said letter. I also provide an audio file where I pronounce each letter and word.

How to pronounce the alphabet?

An easy start is to listen to the alphabet song and an alphabet video such as this one.

If you need help with words, think the easiest tool to mention is the website How to pronounce.

I also created a playlist on my Youtube account where I gathered videos discussing pronunciation in French.

Our favorite technique to learn it is to sing : we sing the English and then French alphabet with the same tune.

Do you know the French alphabet already ? What are your tips and tricks to learn it ?

French – English Alphabet cards

Beautiful alphabet cards to learn French with each letter (with English translation).